March 2007 © Janet Davis

When we finally entered Tarangire National Park

late Tuesday afternoon, we were more than ready to put our feet up but we still

had a fair distance to drive before we

reached our lodging for the night.

Fortunately, the sight of the legendary baobab trees dotting the

landscape on either side of the rough road in gave us something quite

spectacular to contemplate.

had a fair distance to drive before we

reached our lodging for the night.

Fortunately, the sight of the legendary baobab trees dotting the

landscape on either side of the rough road in gave us something quite

spectacular to contemplate.

With its massive trunk and squat, rounded canopy, the baobab (Adansonia digitata) looks more like a giant caveman’s club than a graceful tree. Yet that sturdy bole, those thick, gnarled, ascending branches and the relatively sparse array of leaves tell us something important about the tree’s survival strategy. Like cacti and other succulent plants, the baobob’s trunk conserves abundant water to last through prolonged dry periods. It thus becomes a popular stop for thirsty animals like the elephant, which can inflict serious damage on the bark and cambium layer by rubbing on the trunk to release the sap. Although baobab roots rarely exceed 6 feet in depth, they spread out over an area far greater than the tree’s height. This allows the root system to maximize its absorbtion of water from the short, infrequent bursts of heavy rainfall that penetrate only the upper surface of the soil. Baobabs further adapt to drought by shedding their leaves, and though this was supposedly the dry season, the unseasonal winter rains had enabled them to hold onto their foliage. Had the trees been leafless and the branching more visible, we might have mused on the ancient African legend describing how each type of animal was assigned responsibility by the gods for planting one tree. The hyena, vexed at being the last in line, planted his baobab upside-down with the result that the roots stick up in the air, instead of in the soil where they belong. (Read more on the baobab.)

Tarangire is the third largest

park in

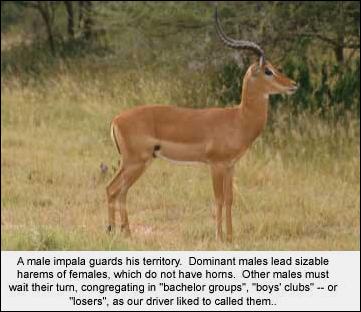

The drive into the park was our

introduction to the shy, graceful impala (Aepyceros

melampus) and specifically to the “boys’ clubs”,  “bachelors” or “losers” that form herds of up

to 30 redundant young males shut out by the dominant male impala at the head of

large female harems. Impalas are mid-sized African antelopes and among the most

common animals – and prey - on the African savannahs. The beautiful, ringed horns of male impalas

curve backward and are the weapons of choice between competing males during the

rutting season.

“bachelors” or “losers” that form herds of up

to 30 redundant young males shut out by the dominant male impala at the head of

large female harems. Impalas are mid-sized African antelopes and among the most

common animals – and prey - on the African savannahs. The beautiful, ringed horns of male impalas

curve backward and are the weapons of choice between competing males during the

rutting season.

Just as we’d had quite enough driving for the day, the vans pulled into the Tarangire Sopa Lodge where we were greeted with refreshing drinks, registered and headed to our rooms. Cocktails and a trip briefing by Philip, our Safari Director, were followed by dinner and an early night to bed.

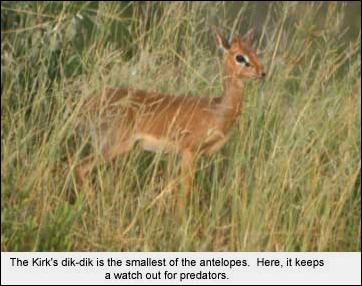

Wednesday morning’s game run featured more birds: a female Maasai ostrich (Struthio camelus masaicus), helmeted guinea hens, a tiny cinnamon-chested bee-eater and our first superb starlings, common as sparrows but oh-so-beautiful with their shiny blue feathers. A Kirk’s dik-dik (Madoqua kirkii), the smallest of the antelopes, was seen through tall grasses guarding his turf. This is accomplished by a daily application of urine or dung and augmented by a spray from scent glands near the eyes.

Giraffes and ostriches posed for photos in front of big baobabs and there were more impalas, this time a male followed by his huge herd of females, each giving a little leap as she crossed the road in front of our van. (When being chased by predators, impalas have been known to leap some 30 feet.)

Large sausage trees (Kigelia africana) were heavy with the

oblong fruit that gives them their name and can be distilled and mixed with

honey to produce a potent local brew.

Over a tributary stream of the

As we pulled into the lodge entrance, a

bright flash of color from the roof caught my eye. It was a dominant male agama lizard (Agama agama) in all his blue-and-red

splendor, soaking in the warmth of the hot shingles while hunting insects. Not far away was a female, looking demure and

suitably drab in her conservative beiges and browns. Agamas are also called African rainbow

lizards. Interestingly, the dominant

male’s bright reproductive colors fade to brown at night; it takes the light of

day to switch on his vivid hues. He also changes color when threatened and during

fights. Like many wild creatures, the

agama lizard has adapted easily to civilization, often preferring to search out

ants and beetles in the rock gardens and pathways of tourist lodges over the

grasses of the savannah. Agamas live in groups of 10-20 individuals, with an

old dominant male and many younger males and females. (To learn more about the agama, check

out this page.)

As we pulled into the lodge entrance, a

bright flash of color from the roof caught my eye. It was a dominant male agama lizard (Agama agama) in all his blue-and-red

splendor, soaking in the warmth of the hot shingles while hunting insects. Not far away was a female, looking demure and

suitably drab in her conservative beiges and browns. Agamas are also called African rainbow

lizards. Interestingly, the dominant

male’s bright reproductive colors fade to brown at night; it takes the light of

day to switch on his vivid hues. He also changes color when threatened and during

fights. Like many wild creatures, the

agama lizard has adapted easily to civilization, often preferring to search out

ants and beetles in the rock gardens and pathways of tourist lodges over the

grasses of the savannah. Agamas live in groups of 10-20 individuals, with an

old dominant male and many younger males and females. (To learn more about the agama, check

out this page.)

A buffet lunch served poolside ended our brief stay at Tarangire. Soon, it was back into the van with guide David as Frederick’s sidekick for another driving day as we drove out of the park and then northwest towards Ngorongoro.

As we passed

Soon, we were climbing up the escarpment of the Rift Valley into the cool Ngorongoro Highlands. This took us into our final leg of the day, up onto the wooded eastern rim of the dramatic Ngorongoro Crater.

Next: Ngorongoro Conservation Area

Nairobi Amboseli Serengeti Maasai Mara Mount Kenya