July 2007 © Janet Davis

Near my summer cottage in

Given its characteristic low topography and the absence of

ambient light in the area, the Barrens was always a favorite destination for

skilled and amateur stargazers who needed  as much darkness as possible to explore the

night sky. But in 1997, following a

campaign led by Muskoka Heritage Foundation director Peter Goering, the

Ministry of Natural Resources of the

as much darkness as possible to explore the

night sky. But in 1997, following a

campaign led by Muskoka Heritage Foundation director Peter Goering, the

Ministry of Natural Resources of the

A Hiking Adventure

For me, the Barrens is a favorite hiking spot with a number of diverse trails from which to choose. So it was that in late May, I was trekking with my son along the paths, photographing wild columbines, witherod viburnum, fringed polygala and other spring-blooming plants along the way. At the site of a large erratic boulder left behind when the ice sheets retreated, Jon stopped to read an interpretive sign explaining the geomorphology while I wandered off looking for things to shoot.

“I’m just going to head down this slope to see what’s in flower,” I said, setting out over the lichens, pine needles and velvety green mosses. Seconds later, I was conscious of stepping on something that felt a little like a soft branch underfoot. At that moment, a strange sound – a combination of clattering and buzzing -- filled the air.

“I think I just walked over a bees’ nest or something,” I said, whirling around, confused at the unfamiliar noise.

“Nope, Mom,” said Jon, pointing at the ground. “It’s a rattlesnake.”

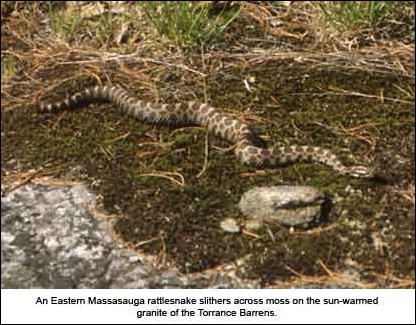

Indeed, I’d stepped on the upper body or head of a poor

Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus

catenatus catenatus),

About the Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake

According to

Massasauga means “great river mouth” in the Chippewa

language, a clue to their normal wetland habitat near rivers and lakes. The

snake’s range is from central

During the summer months, the Massasauga rattlesnake often frequents dryish upland habitats such as the rocky outcrops of the barrens; in winter, it moves to wetlands, swamps or rocky areas where it hibernates in an underground “hibernaculum”. It lives on birds, mice, voles and other small mammals; its own predators are raccoons, foxes, skunks and hawks. Breeding occurs from June to September, with 8-20 young born in August. (The term for snakes that give birth to live young is “ovoviviparous). The Massasauga matures sexually in 3-4 years and has a life expectancy of 12-15 years. Old rattles are shed each time the snake’s skin is shed, so do not indicate the reptile’s age.

The snake can grow up to 2 - 3 feet (60 - 90 cm) in length and can coil and strike up to 1/3 of that length, inflicting a bite with its hypodermic-like fangs that may or may not transmit a poisonous venom (60 percent of the time, such bites are not venomous). But if the victim is very young, very old or has a lowered immune system, the bite can be fatal if medical attention is not received. In cottage country, the West Parry Sound Health Centre is the only hospital to keep an anti-venin on hand and also provides an excellent information sheet on Massasauga rattlensnakes.

A safer approach to hiking in snake habitats is to stay on well-used paths and wear long pants and hiking boots when walking through underbrush. For, like you, the Massasauga rattlesnake would much prefer to avoid any sudden confrontations.